Chase Kramer is an architect and not a video game designer.

However, Kramer and many of his team members at TSP, Inc. are proficient at creating digital environments and interactive representations of real buildings that will be built or renovated.

And, sometimes, that skill set draws comparisons to video game design.

“Many of our projects start out in early conceptual design trying to create some visuals to get clients and stakeholders galvanized and excited about potential projects,” Kramer said.

“The same tools we use to help them walk through detailed design decisions later in a project are the same tools we can use to help clients establish a vision for a project that hasn’t even gone through the traditional design process yet.”

Access to visualization technologies like Enscape, Lumion, and TwinMotion helps clients better understand how their space is going to look and function before they move in. For the design team, the visuals enhance internal cohesiveness and collaboration.

Today’s real-time rendering and virtual reality software can take 3D information from models used for traditional drafting conveyance and add a layer of photorealism. The renderings often feature realistic sunlight qualities, reflections, and material textures.

The software also allows users to “move” through a space as if they were walking or flying through it.

“You can create a fly-through video and send that to a client, or you can hook your phone or computer up to virtual reality headsets and look around in real time as well,” Kramer noted.

These digital scenes and environments can be animated with realistic scale figures, furniture, or even food on a table.

“If you’re trying to help tell the story about a certain design approach or what the client’s vision of the project is, adding some ‘entourage’ or realism with people or objects to a conceptual space is really helpful,” Kramer said.

Much of the rendering and virtual reality software is compatible with TSP’s building information modeling software and offers a significant upgrade in accessibility and ease of use from what was available for visualization even five years ago.

Different rendering software options also have different strengths, Kramer said.

“There are different options that allow you to animate people walking, cars driving, replicate weather effects, all sorts of things, which is fun and complicated,” he said.

“Then you really feel like you are becoming a video game designer or movie director because you are creating and telling these little stories within the context of a building project or design,” he said.

Multidisciplinary difference

The involvement of engineers in visualization is a differentiator at TSP because many rendering and virtual reality tools are geared toward architects, Kramer said.

At TSP, architects are not laying out light fixtures, mechanical diffusers, or duct work to convey design intent. They leave that to the experts.

“Our engineers are doing that right from the get-go for the digital models we’re creating,” Kramer said.

“It begins that collaboration process early rather than waiting to get a contract in place with an engineering consultant. They can buy in to the client’s concepts and goals right away and bring their expertise and insight to the table from the very beginning of a project.”

The walk-through capability of the technology also creates a solid bond between engineers and facility managers.

“It allows engineering to sit down with a facilities manager and show them, for example, ‘here’s how you can access the roof,’ or ‘here’s how you can access this piece of equipment in the mechanical room,’” Kramer said.

“With the ever-growing complexity of designs, a floor plan may no longer suffice to walk through a design, and the act of literally walking through the pathway helps our designers bring a bit of empathy to facilities personnel, helping us be even better designers.”

This is particularly useful in large projects such as health care settings, and it helps facilities and maintenance personnel know how to best interact with the building.

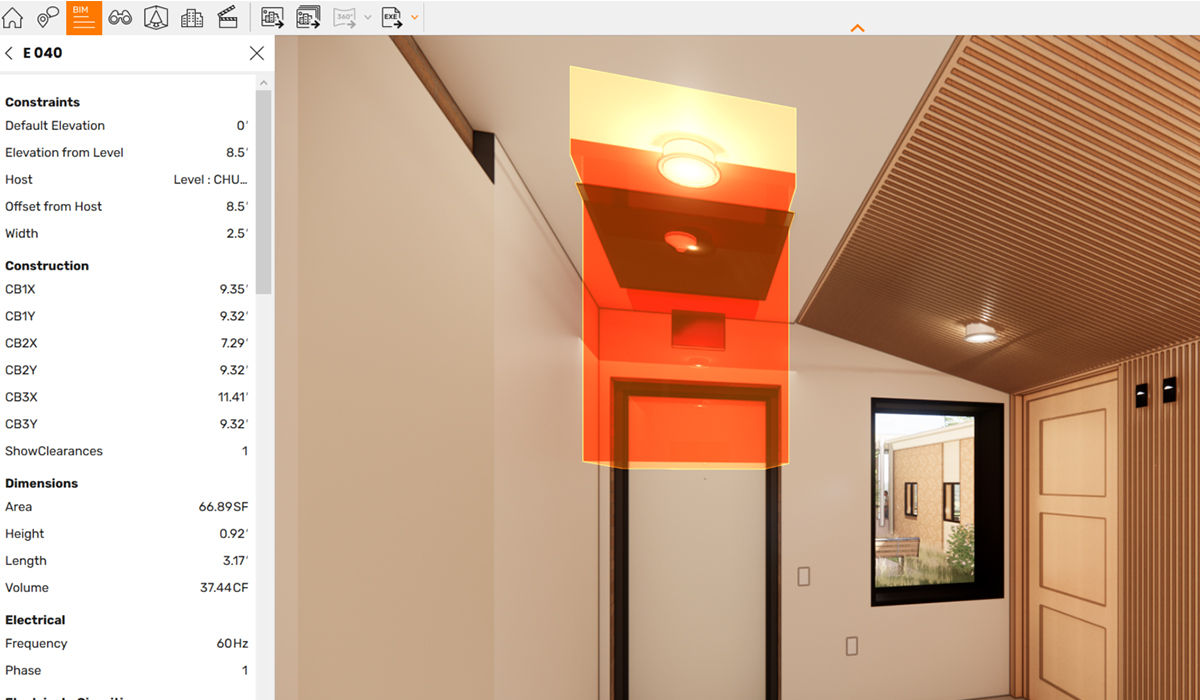

Internally, this approach provides additional safeguards in determining design coordination because engineering is already integrated into a model.

During a virtual walk-through, for example, items sticking through a ceiling become very obvious. The team quickly can determine something is wrong and address the issue.

“Oftentimes, we’ll be able to catch when ducts are too low or ceilings too high, and we can even click on those items in the visualization software to see what they are,” Kramer said.

Helping clients meet goals

Kramer joined TSP in November 2013. Last year, he was named TSP’s firmwide director of design.

The position was created to place more emphasis on achieving design excellence for clients from start to finish, bringing Kramer’s experience and diverse arts background to a greater number of TSP projects.

To that end, Kramer looks forward to incorporating visualization technology on every project to help clients envision and reach their goals.

“This technology results in better conversations and design decisions with the client when you have the proper visualization of that design intent,” he said.

Kramer enjoys working on designs that require fundraising, and high-quality renderings can help build support.

He recently has been working with Augustana University on a small renovation project related to Dolby Atmos immersive sound technology.

Construction will begin this summer on the first phases, but before drawings were ready, TSP provided Augustana a conceptual rendering of what the space could look like to use in a meeting with a potential donor.

The meeting and the images TSP provided helped convince the donor of the important investment, which is now moving into the next stages of design and construction.

Click here to see an example of what was produced.

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, Kramer and TSP team members helped Peace Lutheran Church develop a conceptual master plan to help address the congregation’s ministry needs.

As part of that effort, renderings were developed of the spaces most likely to positively impact fundraising, and a flyover video was generated of the potential outcome of the entire master plan.

This helped generate enough interest and funds from the congregation to kick off phase one of the project, currently under construction along West 41st Street.

Click here to see an example of the video flyover that was developed for Peace Lutheran Church.

Kramer notes that a beautiful visual concept does not mean that all project challenges, including timelines, are resolved immediately.

“A lot of the priority with renderings is making it look right, but all of the details for construction aren’t necessarily figured out or fully designed, so you still emphasize the schematic realm by relying on intuitive and traditional visual cues of a hand sketch or other methods that imply a rough-draft quality to the image,” he said.

“The software even has different ways of handling this, with heavy outlines like a drawing or photo filters to impart a hand-drawing look – all in an effort to establish that this visual is just a stepping stone to a more detailed, finalized design solution.”

Using technology to convey a project still in development is where Kramer returns to the video game design comparison, with one major distinction.

“We’re obviously creating digital models designed with construction means and methods in mind, so they’re actually buildable,” he said.

“While they are used to create the sense of an idea or vision for a project, they’re not just for show to create purely an environment like a video game; they are just one step in helping clients reach their goal of a new building or space.”